Disclaimer: To understand this post you needn’t be good at chess. Although it will be helpful to familiarise yourself with the rules of chess once.

Chess is an old game. Its predecessor Chaturang is at least 1400 year old. The modern version of chess came into being around 1400s. This game has captivated our imagination for a very long time indeed! So it is safe to say no one has quite ‘figured out’ chess. We equate chess with intelligence. Winning at chess requires strategic planning and foresight. Thus it seems unlikely that winning chess can be reduced to memorization of a strategy.

In 1913, the German mathematician Ernst Zermelo published a paper titled “On an application of set theory to the theory of chess” and spawned the field that we today call Game Theory. In essence he proved the following :

“In chess either black has a winning strategy , white has a winning strategy or both sides can at least force a draw.”

Wait a sec… what does a ‘strategy’ even mean?

Perhaps at this point we should make it clear what we mean by a strategy. Imagine a huge piece of paper on which all the possible situations that you can encounter in a game are recorded along with what move you should make in that situation. This can be made precise by using sets and functions but that will not significantly add to our understanding. A strategy is called a winning strategy if by following it winning is guaranteed no matter what the opponent does.

The second part of the statement deserves an explanation. “both sides can force a draw” means the following: There are strategies for White and Black such that if they both follow those strategies the game ends in a draw and if any one of them deviates from it the other one wins.

But does it really prove anything?

Before discussing the proof of this theorem let us think about its implications. If either white or black has a winning strategy then winning is just a matter of memorizing the strategy and the outcome is determined even before the game starts. The third possibility is a bit more interesting. If ‘both sides can at least force a draw’ then players that are aware of this strategy will not deviate from it. If white deviates from it black will use his strategy and win and vice versa. So for two players playing optimally, the outcome is predetermined.

The proof

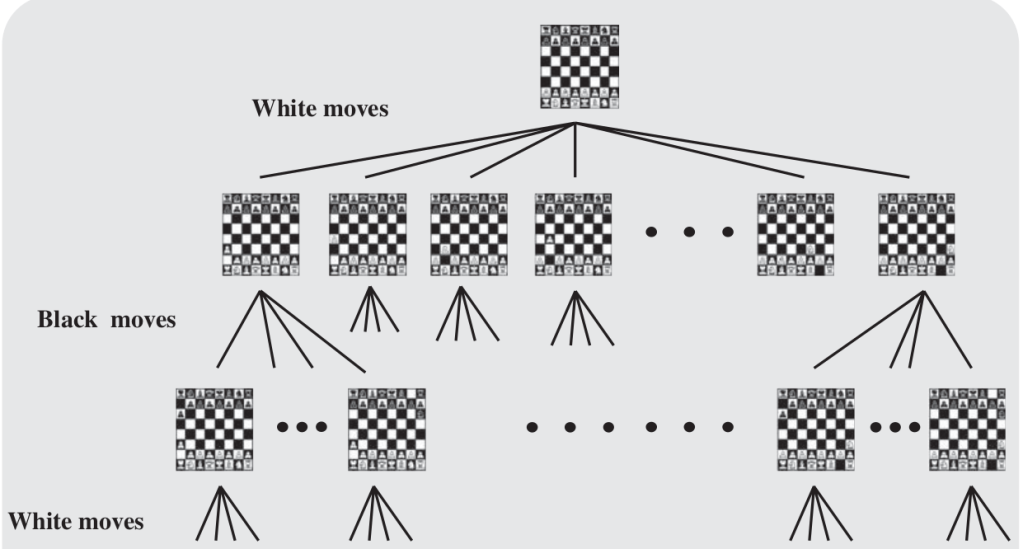

To understand the proof we will need to have some way to represent all possible games that can happen in a chess match. White goes first. How many different opening moves can he make? He can either move a pawn by one or two positions or he can move any one of the knights to either left or right. As there are 8 pawns in total pawns can be moved in 16 ways and two knights that can be moved in 4 ways. Thus there are 20 possibilities for White’s opening move. Now for each of those openings, Black can respond in only finitely many ways. (Never mind how many!) To that White can respond in finitely many ways and so on. We can visualize this using a diagram such as the one given below. It is called a game tree. At the root of this “tree” is the chessboard arranged in the starting position. Below it are all the moves that white can make. Below that are all the moves that black can make in response and so on. Any real-life chess game will follow one path starting at the root vertex all the way to the bottom until there is a checkmate or a stalemate. So it is not difficult to see that our tree will end and not go on forever.

At this point it is helpful to get familiar with certain terminology regarding trees. The individual points are called nodes. If two nodes are connected directly by a line then one which is above is called the parent node and the one which is below is called the child node. The node at the very top is called the root node. By our previous calculations the root node has 20 children.

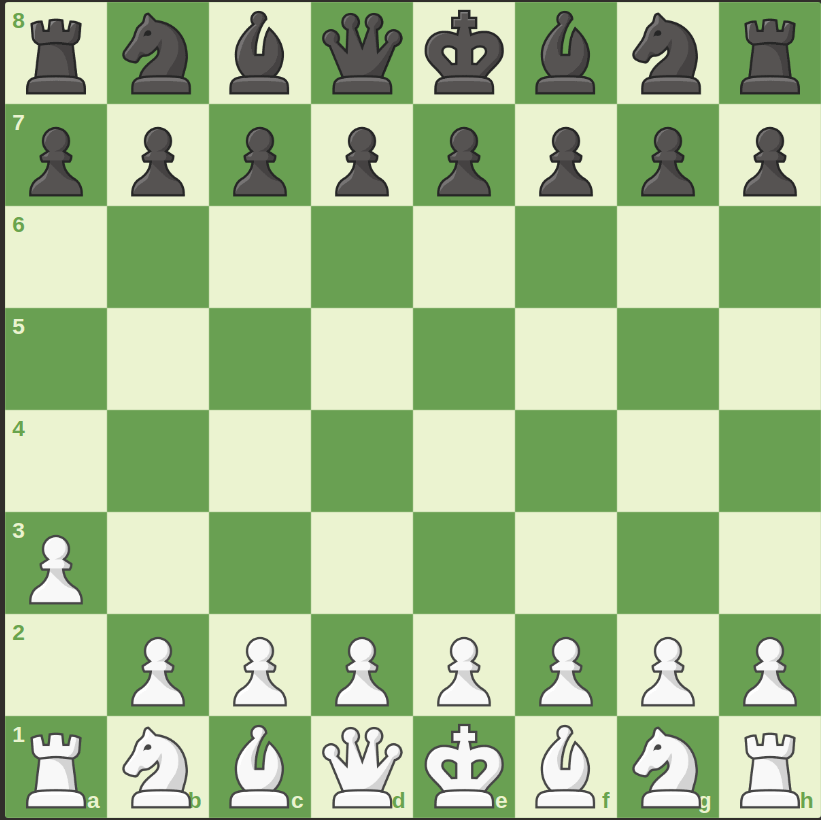

Now we treat each node as a separate game. For instance the the first node in the corresponds to a game in which the starting positions of the pieces is as given below and in this game black goes first. We will call it a subgame.

It’s almost as if someone started a game of chess but left midway and now you have to play at his position from this point onward. So the stage at which he left the game becomes your starting point.

The proof proceeds via induction. We will prove the following:

” If the statement is true for all the subgames corresponding to the child nodes of a given node then it is true for subgame corresponding to the node itself. “

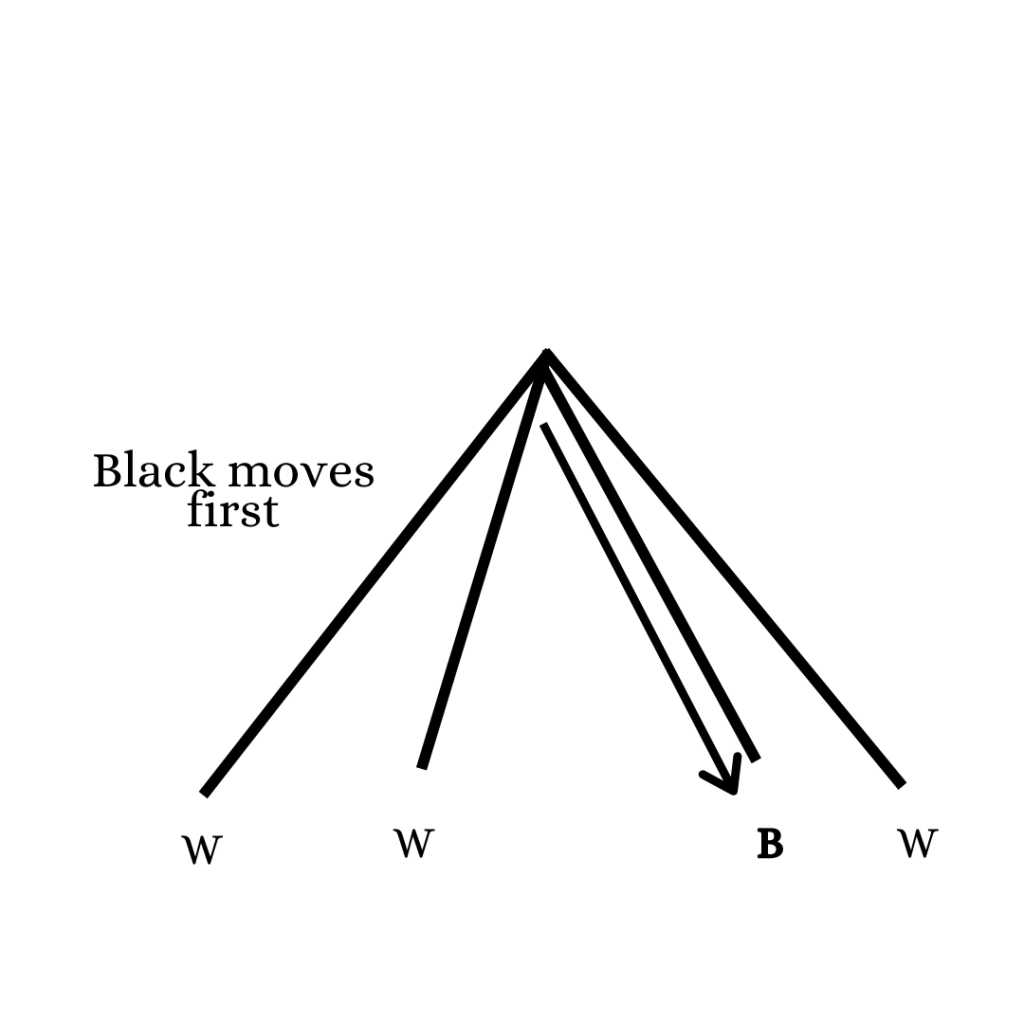

This is the so-called induction step. In a way, we are going from the bottom to the top. Given any node either white plays first or black plays first in its subgame. Let us assume for the moment that black plays first in the node given to us. Let us assume that the statement is true for all the nodes. It is possible that for some child nodes Black has a winning strategy, for some White has a winning strategy and for some nodes, there is a drawing strategy for both of them. We will define the game value of a node to be W if White has a winning, B if Black has a winning strategy, and D if both have a drawing strategy. We split this into three cases.

a) For all child nodes the game value is W: In this case, it doesn’t matter which move black makes. In this case, White has a winning strategy.

b) There is at least one child node with game value B: First Black moves to the node in which black has a winning strategy. And then onward he follows the winning strategy of the child node. So in this case black has a winning strategy.

c)There is at least one child node with game value D but no node has game value B: In this case black can avoid losing by going to the node with game value D. From here on he follows the drawing strategy of the child node. In this case both black and white can at least draw the game.

The arguments are similar in the case that white moves first. Just interchange ‘Black’ with ‘White’ and W with B A proof via induction is complete only after the base case is proven. Here base case corresponds to the very last nodes in our tree. A game ends only when either black or white is checkmated or a stalemate. But for these nodes, the statement is vacuously true! The winning strategy here is ‘do nothing’!

Endgame Tablebases

Everything said and done it is not likely that this winning (or drawing) strategy will be found in the near future. The proof suggests a way of actually finding the game value of the root vertex by starting at the bottom and going up. The trouble is that the tree is very large. Even with the help of the fastest computer, it would take a really long time to go to the very top. Even if it is found, memorizing it would be next to impossible for a human.

Finding the game value is well within reach for ‘subgames’ which are lower down in the tree. Indeed chess puzzles with only a few pieces are popular among chess players. These are sometimes called endgames. People have determined the outcome of a large collection of endgames. Earlier only 5-piece chess endings were available i.e endings of games with only 5 pieces left on the board. Later Convecta Ltd. announced that it has tabulated all endgames with 7 pieces. The size of all tablebases up to seven pieces is about 140 TB!

Reblogged this on REFLECTIONS.

LikeLike