By: Algeva, Alchemist

Observe and learn; that’s what science is. We listen to birds chirping, cooing, and some of them even singing but have you ever wondered why they do so and why they sing specific songs? Now, that is where observational science comes into play. We will look into this very intriguing yet little explored area of interest.

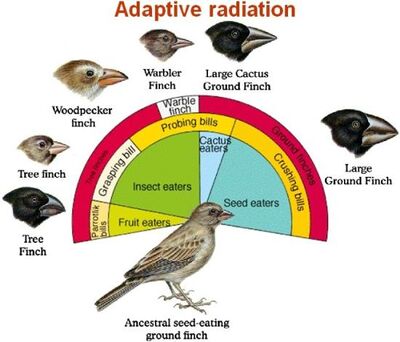

Heard of Darwin’s finches? They are a particular group of birds native to the Galapagos Islands and ever since their discovery continues to fuel research in evolutionary biology. They constitute a typical example of what we call an ecological sample space. Several scientists have worked on the ecology of these species from Great Darwin to the couple-scientists Grants. Enough with the background info, let’s dig into the science of bird songs. Now, as you may know, any special skills contribute to an added advantage for a person over others in terms of finding a mate, right? The same goes for nature. Female birds find male birds who sing more attractive than those who don’t. Given a set of singing birds, those who sing better have the edge over those who sing moderately. I will set an example using finches so that you get a stronghold of the concepts. The credit of the works goes to Peter and Rosemary Grant (Grants) who explored the ecology of the Galapagos Island, Daphne Major.

Only male finches do sing. Sons learn songs from their father. Now the learning process is a little complicated. During early learning, sons produce a reliable copy of their father’s song and later on increase the frequency so that they sing a slightly different version of their father’s song yet identifiable by potential females. Singing can act as cues for mating, and the song constitutes signals for mates. From the wide array of signals that the female receives, she sits down and chooses one and selectively mate with that male. That is okay, but why let females choose males, why not the other way around? That’s because, female ova (eggs) are expensive; they produce one or so in each reproductive cycle (menstrual cycle, a more familiar term). Whereas the sperms are cheap. Males produce millions of them in each cycle; it is abundant and always available. So as is evident from the cost-benefit analysis, females get to choose whom should she mate with. Now all that matters is the choice. There is fierce competition among males to be selected by the female. Therefore they try to maximize their skills, and the song is just one of them (this is the same reason why male peacocks have beautiful feathers). Let’s get back to the song learning process. While learning a song, the finches have to make sure that they are not deviating from the father’s song (results in immediate rejection by females) and also that the songs of different species are distinguishable. Some birds covet females of other species by imitating their song and producing a duplicate copy of it to deceive the female. Now there is no problem with that as long as the hybrid children are more fit to the environment (fitness as in better adapted to the severities) and capable of outgrowing others in occasions of food scarcity, droughts or any other ecological pressures for that matter. If the hybrids are unfit to live, this interbreeding of finches of different species must be prevented by installing some sort of premating barriers. Singing a different song can act as such a barrier. Thus females can identify males of own species by recognising the species-specific song. How can each species sing different songs, or who instructed them to do so? Nature it is. Different species feed on different fruits and differently sized seeds so that there is less competition for food

(This is a direct outcome of competitive exclusion and competition-driven speciation, interested readers are encouraged to refer to the same). Now each species has beaks that are adapted to consume the particular food that it is supposed to. Therefore different species have different beak

structures, sizes and length.

Finches with shorter beaks produce songs of higher frequency compared to those with larger beaks due to their inability to open and close beaks rapidly. Also, each note of the song is longer in duration for birds with larger beaks than for birds with smaller beaks. Natural selection on food types has, therefore, influenced the features of the song that the corresponding species sang.

Body size also modifies song features. A larger finch will have a larger syrinx volume, and hence vibrations of the vocal cord are confined to a larger volume. This changes the song frequency and notes. Any physical changes to the song producing apparatus can also lead to a different song.

Nature has also set up mechanisms to prevent instances of song imitation and identity thefts. In a peak shift mechanism, sons deliberately tune the frequency of songs learnt from the father by rising the trill rate (number of notes produced per unit time) and make the song identifiable to females at the same time distinguishable from imitators.

All of this has to do with reproductive success. Songs enhance the chance of meeting and mating, thus increasing the reproductive success. Reproductive success is equivalent to fitness. And the more fit a species is, the more likely is its survival; as it goes, “survival of the fittest”.

The findings stated above are the results of dedicated long-term research conducted by Grants. Let’s now learn something about them!

Peter R. Grant & B. Rosemary Grant are members of a select scientific community, who have seen evolution happen right before their eyes. The renowned evolutionary biologists are known for their long-term work demonstrating evolution in action in Darwin’s finches on Galapagos Islands. For the married couple, evolution is a concept that is real and immediate and sometimes quite fast, unlike Charles Darwin’s idea of slow and accumulating changes over large timescales or periods. The Grants observed evolution with cameras, measuring instruments, advanced genetic analysis techniques. Every year since 1973, they have spent several months capturing, labelling, and collecting blood samples from the finches while enduring baking days and sweltering nights, cooking in a cave, sleeping in tents, and somehow sustaining themselves on a tiny island deemed inhabitable, named Daphne Major. The Grants studied the finches for 40 years in contrast to their original plan of 2 years, showing that natural selection can be observed within a single lifetime or a couple of years, and it can happen even rapidly in populations. They have also explained mechanisms by which new species arise and how genetic diversity is maintained in natural populations. Peter Grant is currently Emeritus Professor of Zoology, and Rosemary Grant is currently Research Scholar and Professor of Emeritus Zoology Princeton University since 2008.

Born in southern London in 1936, Peter had relocated to the English countryside on the Surrey– Hampshire border to avoid bombings during WWII at the age of four. He grew up fascinated by the abundant diversity of organisms in the world. The early experience of watching birds and collecting butterflies helped shape his career in ecology and evolutionary biology. After graduating from Cambridge University in 1960, his wish to experience life and his love for the natural beauty of British Columbia pushed him to pursue his Ph.D. at the University of British Columbia, Canada, where he soon met Rosemary. As a part of his doctoral degree, Peter focused on the degree of interconnection between evolution and ecology, prompting the couple to study how competition for food among terrestrial birds helped cause an evolutionary change in beak size on the Tres Marias Islands in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Mexico. This work played an essential role in their findings on Darwin’s finches. Peter obtained his post-doctoral fellowship at Yale University, where he studied with the father of modern ecology, G. Evelyn Hutchinson, who was responsible for advancing his intellectual development. Later, Peter returned to Canada, accepting the position of Assistant Professor at McGill University in 1965. Before his appointment at Princeton University in 1985, he also held positions of professorship in universities of McGill & Michigan.

Barbara Rosemary Grant was born in Arnside, an estuarine village along the river Kent in northwest England in 1936. The diversity of organisms in the hillsides, amidst the riot of rare butterflies, along with her field trips to nearby limestone cliffs accompanied by her mother and collecting plant fossils and comparing them with living lookalikes, all helped her to discover the joy of scientific exploration and curiosity at a very young age. This curiosity of the differences in the plants collected paved the way to what became her life’s quest to study natural variation. Her acquaintances with geneticists Charlotte Auerbach and Douglas Falconer was pivotal in shaping her decision to pursue university education – a world dominated by men at that time. She graduated from Edinburgh University in Scotland with a degree in zoology in 1960. Her excitement in teaching made her accept the post of biology lecturer at the University of British Columbia instead of pursuing a Ph.D. immediately. There she met Peter Grant and married him a year later, following which they started their combined journey in the shared passion of understanding the basis of natural diversity. She also held lecturer positions at Yale University, McGill University, and the University of Michigan between 1964 to 1985. After 1980, Rosemary decided to pursue her long-deferred Ph.D. at Uppsala University, where she focused on the patterns and causes of morphological variation in the large cactus finch, G. conirostris, on a low-lying Galapagos Island called Genovesa. After earning her Ph.D. in 1985, she joined Princeton University in 1985 as lecturer.

While at McGill, in between looking for a model organism to test his competition hypothesis and wanting to know why some populations are unusually variable, the Grants decided to embark on a journey to the Galápagos Islands in 1973 after drawing inspiration from Darwin’s Finches, written by the evolutionary biologist David Lack. The trip marked the beginning of their four decades of research, which have helped profoundly understand natural selection and evolution. They have published three books – “Evolutionary Dynamics of a Natural Population: Large Cactus Finch of the Galapagos (1989)”, “How and Why Species Multiply: The Radiation of Darwin’s Finches (2008)”, “40 Years of Evolution: Darwin’s Finches on Daphne Major Island (2014)” – all which depict the monumental work of their lifetime. The Pulitzer winning book, “The Beak of the Finch: A Story of Evolution in Our Time” written by Jonathan Weiner describing the evolution of these songbirds, is based on the 20 years of research and work by the Grants in Galápagos. They are recipients of numerous awards such as the Leidy Award from the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (1994), the Loye and Alden Miller Research Award (2003), the Balzan Prize for Population Biology (2005), the Darwin-Wallace Medal (2009) and the Royal Medal in Biology (2017). They have received the Japanese equivalent of the Nobel Prize– the Kyoto Prize in 2009 for their lifetime achievements in basic science.